“A successful check-in is complete when a customer is comfortable and satisfied in their room. Not just when they leave the check-in counter.” — General Manager, Ad Hoc Hotel & Casino, Las Vegas

This was the prompt we gave to 35 participants that joined us recently at Code for America Summit for Prototyping Products and Digital Services 101.

We used this scenario (improving the check in experience at the fictional Ad Hoc Hotel & Casino) to introduce people to the human-centered, service-design-rooted processes we employ to understand a problem, learn quickly, and adjust.

Prototyping helps you answer key questions about how people might use your product or service. When we know a domain really well, it’s hard for us to step outside of ourselves and imagine how someone else might approach it. Those implicit assumptions, if left unchecked, can be costly in the long run. Prototyping and testing early can help surface incorrect assumptions, allowing you to make more informed decisions about the direction of your product.

This discovery process is critical to making sure that the government digital services we build support our social infrastructure services as effectively as possible. This fast, iterative process can save agencies time and money. It’s much less expensive to discover your prototype isn’t solving your users problems than it is to invest in the full engineering lifecycle of a product before you get the chance to get feedback from your users.

The workshop

For our three-hour workshop, we led participants through a prix fixe menu of activities that built up to a testable prototype. We then used that prototype to conduct user research with users we recruited in advance. We introduced participants to nine or more activities, culminating with this question: Were you able to validate your hypothesis?

This workshop was guided by a presentation where we introduced each activity and kept track of the time. At each table, we had a table facilitator supporting 5-7 workshop participants. Each participant was given a packet of materials with information about our example scenario as well as basic instructions for how to conduct each activity on their own.

The scenario

We built out a basic fictional scenario that we thought everyone would have experience with.

At the Ad Hoc Hotel and Casino, customer satisfaction ratings are at their lowest right after they check in. How might we increase satisfaction ratings for the following key groups: business travelers, families with kids, couples, and large groups (family reunions, weddings)

Problem definition

The problem definition phase of work is critical to developing a meaningful hypothesis that can be designed, prototyped, and tested against. We presented each table with a unique persona and a customized problem statement from “the management.” They also had a high-level service blueprint that included some basic pain points. Teams used this information to select a relevant pain point, break it down with a 5 Whys exercise, and then develop their hypothesis.

Our business traveler team, facilitated by Rachael Rouche, Principal Product Manager at Ad Hoc, identified “room readiness” as a primary pain point that, if resolved, would address their personas’ needs best. After working through one 5 Whys path, there was an audible, “Ohhh… That’s the five whys…” from one participant. Then they dug in to explore the rest of their pain point more deeply. Ultimately, they developed this hypothesis:

If we can improve housekeeping staffing, we can reduce the number of times that rooms aren’t available.

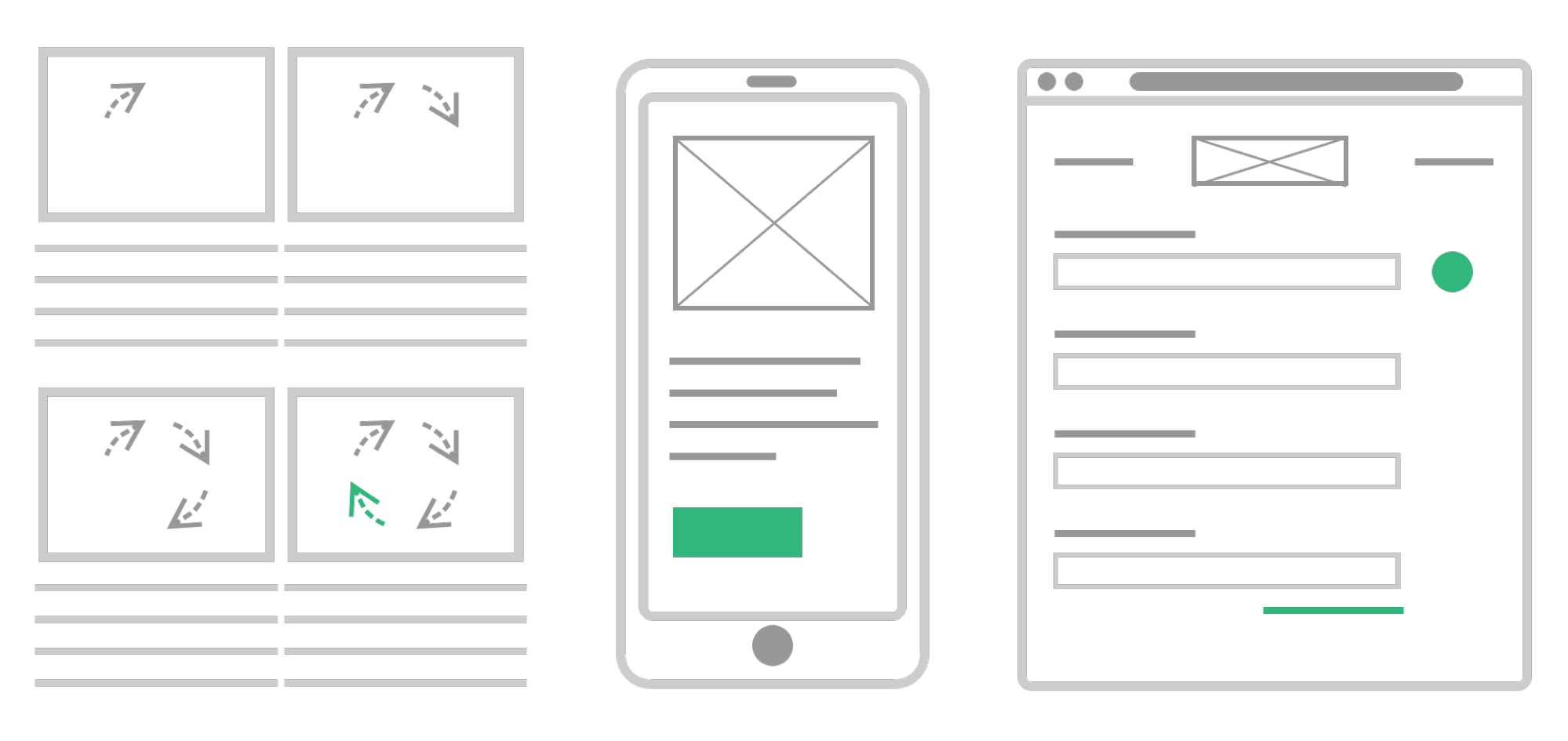

Design

The design phase starts with divergent thinking again, to explore potential solutions for how you might fulfill the supposition in your hypothesis. Participants used a generative sketching exercise to open up their minds to creative ideas. They then narrowed the scope to work on prototypes that focused on just a couple of the most promising ideas. We encouraged them to build their prototypes as either wireframes for digital solutions or as storyboards for service interactions. The team selected one of these prototypes to test.

During generative sketching, Rachel’s team focused on ideas that optimized current staffing by decreasing the number of rooms that needed immediate cleaning. Some of their ideas included: make guests pay for room service, incentivize staff to be more productive by throwing parties if they met quotas, and giving the housekeepers roller blades.

Silly ideas like that last one are important in getting our brains moving. While rollerblades aren’t likely to be the final idea, it might inspire other ideas that focus on efficiency of movement: Moving cleaning materials storage closer to rooms or reconfiguring cleaning carts and waste management to make transitioning between rooms faster.

The idea they chose to focus on for their prototype was:

If everyone had iPads on their carts to dynamically show the top priority rooms it would ensure that top priority rooms were cleaned first.

Testing

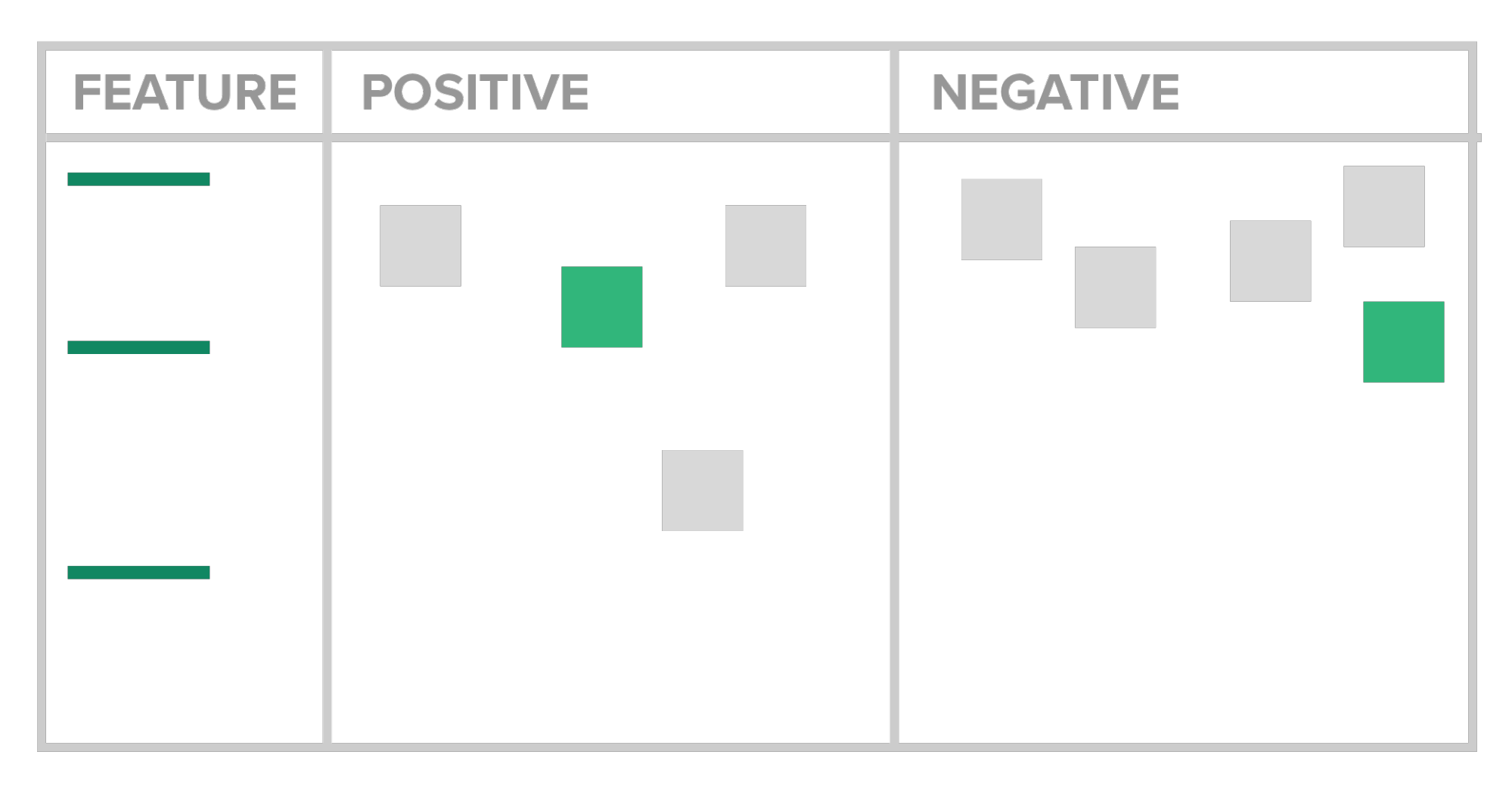

The testing phase is critical to validating or disproving your hypothesis. During this phase, participants worked with facilitators to develop a test plan and a test script. We use these tools to make sure that our feedback sessions with users stay on track and that we end up with outcomes that are meaningful to our original hypothesis.

Facilitators ran these user research sessions, leading users through background questions and interactions with the wireframe or storyboard prototypes. Workshop participants took collaborative notes focused on meaningful quotes and observations. These notes were then categorized into positive and negative groupings. The team later analyzed their collective notes to find common themes.

To give participants an idea of what user testing can be like, we recruited volunteer users from outside the workshop to stand in for the personas we defined for the workshop. This was pretty unusual for such a short workshop, but we knew how critical it would be for participants to get a chance to talk to a real person about their ideas.

During user testing, our business travelers team uncovered an incorrect assumption they’d made about room cleaning. Some rooms are far messier and take more time to clean, and this is not predictable. The user they worked with also expressed concern that integrating iPads into their existing walkie-talkie process wouldn’t make anything faster and might cause more errors.

Rachael’s team analyzed their results with three options. Should they cancel the initiative, pivot, or continue as planned? The recommendation they made to hotel management was:

If you choose to iterate, you will be spending a lot of money building something new that we aren’t confident will work. We recommend hiring one additional person and investigating upgrading the tools and materials the cleaning staff uses for cleaning, such as vacuums.

Results

Our workshop was jam-packed with activities that guided our participants through problem definition, prototyping, and user testing. Participants left our hands-on workshop with an understanding of the power of cross functional collaboration and an understanding of how the design and prototyping process can inform the direction of their product or service. One participant said, “I’ve only had input on the prototypes before but it was extremely helpful to do it myself.”

Next steps

We love quotes like this one: “Great facilitation. Loved that there was someone at each table to help guide the activity.” But we also recognize that just like your product, our workshop should always be evaluated for ways it can be improved. We’re here to make these tools as useful as possible and we’ll continue to iterate on our workshop as we lead it with new communities and learn more about how to make it the best tool it can be.

We plan on conducting this workshop again in the Washington, DC area in the coming months. In addition to this 101 Workshop, the Ad Hoc Innovation team can help you apply these methods to your work. We offer an introductory 2 hour workshop as well as our longer 2- and 5-week sprints.