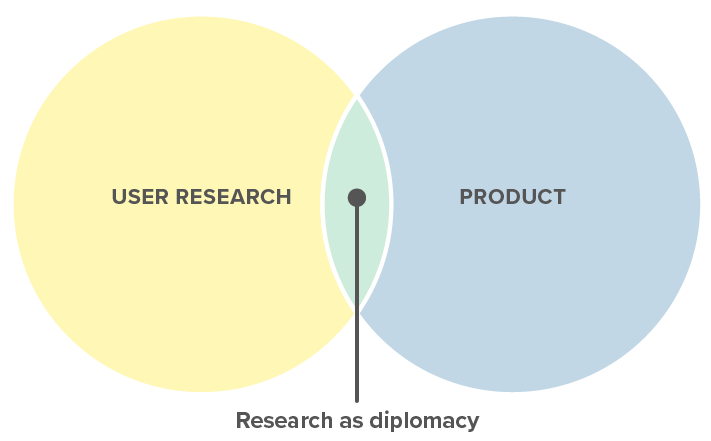

Research as Diplomacy: The marriage of research and product

However, products designed without understanding the problem space and the ecosystem they interact with can end up doing more harm than good and can put stakeholders in difficult situations (squandered budgets, detrimental unintended consequences, increased security risks). Reframing the research step and using it to bring stakeholders’ concerns to the forefront instead of pushing past them can turn research skeptics into research advocates. We call this approach Research as Diplomacy.

Research as Diplomacy is the intersection of product and research. It’s centered around a common understanding that successful products are not only those that meet KPIs but are also the ones that come from deep listening, building strong, authentic relationships, and understanding the perspective of stakeholders and users.

We design and maintain APIs to process appeals at a government agency. Our stakeholders are lawyers and business professionals who do highly nuanced, interpretive-rich work. And their work is not easily translatable into API architecture. Here’s how we’ve used Research as Diplomacy to build APIs for a challenging problem space.

What is Research as Diplomacy?

Building technology for the public sector, as Cyd Harrell describes, implies working closely with experienced civil servants who understand government systems, and in many cases, have built these systems. These relationships are key in building successful digital products that work for complex policy and regulatory contexts.

Initially, the research practice at Ad Hoc coined the term “Research as Diplomacy” to describe the sometimes invisible conflict resolution and relationship management skills that researchers bring to their work. Since then, we’ve expanded the definition and developed it as a framework to work collaboratively with our stakeholders.

Research as Diplomacy combines the tools and analytical power of research with the strategic outlook of the product discipline to identify, build, and nurture key relationships with stakeholders, and users, who have a deep understanding of these contexts.

When to use it?

Research as Diplomacy is a strategy for helping change stakeholders’ minds when they’re resistant to spending time and effort on research. It can also be used when a stakeholder is resistant to the project in general.

As mentioned earlier, we developed this approach through our work with lawyers who review appeals for benefits decisions for a government agency. In their day-to-day work, our stakeholders face the difficult challenge of developing repeatable and fair procedures to intake a high volume of appeals from people who disagree with the agency’s interpretation of the evidence they submit to support their claims.

This work is interpretation heavy; it requires a deep understanding of legal and regulatory frameworks in order to assess whether a claim is valid or not. And because this interpretive work is highly nuanced and subtle, these stakeholders are often apprehensive of external software teams who may not understand the full context of the work. As a result, they probe and poke holes into digital solutions aimed at managing these intake processes. If the answers are not satisfactory to them, these stakeholders will delay launch or outright stop the software development work. From their perspective, and rightfully so, the stakes of getting digital products wrong are too high.

Research as diplomacy has been an effective tool for our team to build these relationships, understand nuance, earn trust, and collaboratively define how to move products forward.

Through this experience we learned that both authentically listening to stakeholders, and making stakeholders feel heard from the get-go goes a long way. In this specific case, we leveraged the research process to open a channel of communication and understand our stakeholders’ concerns. Through these conversations, we got a better grasp of the constraints that this group was working under and why the initial technical solution proposed would not work in this context. We then proposed the next best possible solution given those constraints, and we agreed on a roadmap to iterate and keep pushing the product in a direction that will ultimately benefit the users of these government programs.

How to implement Research as Diplomacy

After this initial experience, and as we started working with other stakeholders within the agency in the same problem space, we formalized a Research as Diplomacy framework. We continue to iterate on the approach and remain nimble when circumstances demand a change of pace, but we want to share some guidelines that have proven to work.

1. Conduct discovery research early on in the delivery cycle.

Discovery research takes time and iteration. To ensure that we have the answers we need ready for engineers to start the development work, research and product work closely to turn the unknowns in the product roadmap into research questions. We then create research plans based on those questions and work together to define the priorities of the research work.

At the start of the project, we hold a Kick-off meeting that includes a mini listening session with the stakeholders. This listening session is structured similar to a research interview and led by the researcher. This is our first opportunity to understand the stakeholders’ perspective and find out what their concerns or resistances may be. The types of questions we include are:

- What do you see as the biggest pain points of the current process?

- What are some roadblocks or gotchas you think we may encounter with this project?

- What does the success of this project look like to you?

- Is there anything else you want to ensure we take into account?

By starting the relationship with stakeholders by listening and valuing their concerns, it helps disarm their resistance and lays the groundwork for building a relationship based on trust.

2. Talk to any stakeholder or SME who wants to share knowledge.

When researching complex processes or policies, we first review federal regulations and procedure manuals detailing the processes we’re working with. Based on that, we put together a process flow with our initial understanding. Then we schedule research sessions of about 45 minutes. We make room to talk to anyone who wants to talk to us, even if they don’t directly handle the part of the process we’re working with.

In addition to the initial listening session, we include our stakeholders in our list of research participants when applicable. We also work with our stakeholders to further fill out the list of participants so we ensure they are bought into our research plan. By making the time to talk to as many stakeholders and Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) as we can, we’re able to paint a rich picture of the context of these processes and the rationale behind how processes are set up. We also share the process diagram with stakeholders who help us revise it, add to it, and understand how the different parts fit with each other.

This approach does mean talking to more people than usual. Even if you talk with multiple people with the same experience or perspective, the act of talking with them and listening will help gain their trust and buy-in. As mentioned above, mistrust of a new team working in a problem space can often be based on stakeholders’ belief that the team does not understand the complexity of the problem. By listening to as many stakeholders and SMEs as possible (and feasible), this helps build trust with the stakeholders that your team respects the complexity of the problem and is putting effort, in the form of research, into understanding.

3. Deep Listening

We record all the interviews we conduct. We transcribe all of these interviews and keep an archive. In the process of transcribing, re-listening to a session, and slowing the recording to make sure we understand specialized terms, we spot themes that help us understand why our stakeholders have set up the processes they have, why they work the way they do, and the constraints under which they operate. We often rely on these transcripts to find answers as our engineers start the development work, and we follow-up by email with participants if we can’t find the answer. We also use the transcripts archive after projects have ended to design new research to make sure that we’re adding to what we know instead of replicating it.

We also encourage members of the development team to attend the research interviews as observers or to watch the recordings. By having our team members hear the pain points first-hand, it helps to ensure they understand the problems and also puts them in a better position to brainstorm solutions.

4. Include stakeholders in research with users

After listening to stakeholders, and getting a grasp of processes from their point of view, we talk to the users of these services to understand their experience and data needs to ensure we’re exposing the right data. We invite stakeholders to observe these research sessions, we share research plans and conversation guides with them and encourage them to also ask questions, and we ask them to help us recruit participants. By getting involved, they see first hand where our analysis and recommendations are coming from and understand better how their own processes affect the users they serve.

If a stakeholder’s resistance to research is based in believing they already fully understand the problem, attending the research sessions can be a way of showing there are aspects of the problem they had not accounted for or did not understand. This helps them see the importance of research.

5. Frame research results in their own language

In transcribing and analyzing the transcripts, we also pay close attention to the terms that stakeholders use and how they use them, mainly focusing on understanding how they frame their concerns. We usually give research readouts where we present the results of research, both of what we gathered during the stakeholder sessions and the user sessions. We frame our findings using the same frames that our stakeholders use, and present back to them what we understand as the context and constraints they have to work with. In these readouts, we leave room at the end to ask questions, offer clarification, and disagree.

When applicable, we also create a version of the research readout to share with all internal research participants. This helps them understand the impact their feedback had and foster a stronger relationship when we need to reach out for follow-up questions.

6. Show stakeholders how their contributions were taken into account in the design.

In the readout sessions, we offer recommendations and examples of how our APIs will help solve problems that stakeholders and users experience. We ensure that we’re connecting the dots between our understanding of the context, the findings, and how we think our recommendation will interact with the process.

For example, in a recent project, we found that the context of the work requires users to strictly adhere to the written regulation so their appeals meet all requirements and are successfully processed. We also learned that the agency was receiving many duplicates, and this was creating a processing backlog.

The written regulation did not specify all the different channels that could be used to submit appeals, including digital channels, but users had heard in informal spaces that they could use these digital channels. To ensure the appeals were received, they submitted the appeals electronically, and then submitted copies through all the different channels specified in the regulation. We offered recommendations on how to design the API to reduce duplicates, and we also recommended that the agency should update the regulation to include digital submission. This recommendation echoed the suggestions that we had heard from users and stakeholders and helped boost those voices. As a result, the regulation was updated, helping to eliminate confusion on how to properly submit appeals.

Conclusion

By reframing how we approach research at the start of a project, we have found success gaining trust and buy-in from stakeholders that were previously hesitant. Using research as a framework for starting a project with a listening mindset helps diffuse tensions and improves trust. Stakeholders’ concerns are often rooted in very real issues that will affect a problem space and therefore what is built to address the problem. By using a research-based approach to uncover what makes a stakeholder hesitant or untrusting, you can not only better understand your problem, but also get stakeholders bought-in to the research process itself.

Related posts

- The new Ad Hoc Government Digital Services Playbook

- Four myths about applying human-centered design to government digital services

- Our four day discovery sprint with San Jose

- Using CX to align goals for improved service delivery

- Aligning human-centered design and Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe)

- Teamwork makes the dream work: Managing effective product analytics projects