Improving government services, by design

Among the list of required elements in Circular A-11, section 280 that a federal agency is expected to include in their CX management is service design. The guidance describes service design as

Adopting a customer-focused approach to the implementation of services, involving and engaging customers in iterative development, leveraging digital technologies and leading practices to deliver more efficient and effective interactions, and sharing lessons learned across government.

At Ad Hoc, we support a number of federal digital services and work with agencies to build the digital interactions that make it possible for people to receive federal services — from healthcare to Veteran pensions to early childhood education. Service design is one way we help agencies understand how someone interacts with a service now and find opportunities to improve on that process. We know that in order to build effective software, we need to understand the needs of the people who use the service, as well as the current processes to support them.

Today, we’ll explore the basics of what service design is, how visual frameworks such as user journey maps and service blueprints can help us understand and improve upon service delivery, and how government services in particular can benefit from a service design approach.

What is service design?

Think about the last time you got a new driver license, bought some pants, or picked up some fast food. In each of those interactions, as different as they are, you were receiving a service.

In each of these examples, your goal happens to involve receipt of a product of some sort, too. A service doesn’t always result in your receipt of a product - as in haircuts or doctor’s checkups. But many of our goals and interactions are based on our need or desire for a thing, whether digital or physical. So we often conflate the two - products and services - in part because we use a lot of digital products, and in part because service delivery and product delivery can rely on many of the same skill sets and tools.

For our purposes today, we will use the simple definition that Lou Downe uses, which is that “a service is something that helps someone to do something.” At the risk of being too literal, then, we will say that a product is a thing (either physical or digital) that someone can have or use. We may use many products in our efforts to receive a service, or go through a series of services to receive a product. Because whether the end product is a license that indicates the state’s approval to drive a car, warm french fries, or new sweatpants, each one involves a series of human and digital interactions that occur even before you arrive, in addition to the direct interactions you have with people or tools to get what you need. Those interactions, and your experience with them, can be thought of as the service. And each of these services was designed — however well or poorly — to deliver that product to you. The effort to understand the full process behind your experience and to improve upon it for both you and the organization providing it is called service design. Service design is powerful because it zooms out beyond the development of any individual product to understand the actions, policies, and processes that surround it.

Service design as a discipline has been around for 30 years, but it wasn’t until Lou Downe established the formal practice of service design within the Government Digital Service (GDS) team for GOV.UK in 2014 and started blogging about it in 2016 that the practice started to make its way more broadly into government service delivery. While its adoption has been slower among US government entities, the teams that have started to take a service design approach are seeing just how powerful it can be to improve end-to-end processes.

Evolution or design?

When a service isn’t designed intentionally — when it just evolves over time — the recipient of the service often has a poor experience. If you think of all the jokes out there about the pain of getting a driver license, that’s because the service hasn’t historically been designed to optimize the driver’s experience in the process. Instead, the process has evolved across silos in a complex organization, each silo thinking only about its own process.

This is common, especially in complex organizations like federal government agencies. In any large process with many teams and touch points along the way, it’s easy for individuals to focus on their piece of the puzzle and lose sight of that bigger picture. They may not even be aware of the other pieces of that puzzle. While that natural evolution may meet the need, it will likely contain a lot of tangled, disjointed, and slow processes that result in a poor customer experience and wasted time for the customer and employees. No one wants to spend any more time than absolutely necessary interacting with government services - these services are a means to an end, not the end itself. So how can we make those interactions less frustrating and time-consuming?

This is where service design can help. A team focused on service design zooms out to consider the full end-to-end journey — even if they don’t deliver the full service — and find opportunities to improve and untangle the process for both the service providers and the recipient.

Breaking out of organizational or team silos and taking a more holistic approach requires that a team be empowered at the right level within the organization to do the work of researching, building, and sharing insights to the wider landscape in which the service operates. Service design — and redesign — requires intentionality.

To improve a service, we first need to understand the journey for both the person receiving the service and all the human and digital actions behind the scenes that enable it. We might use a variety of user research methods to understand that process, and each actor’s experience in it, and then map it out. Some of the frameworks we lean on to do this are user journey maps and service blueprints.

Journey mapping

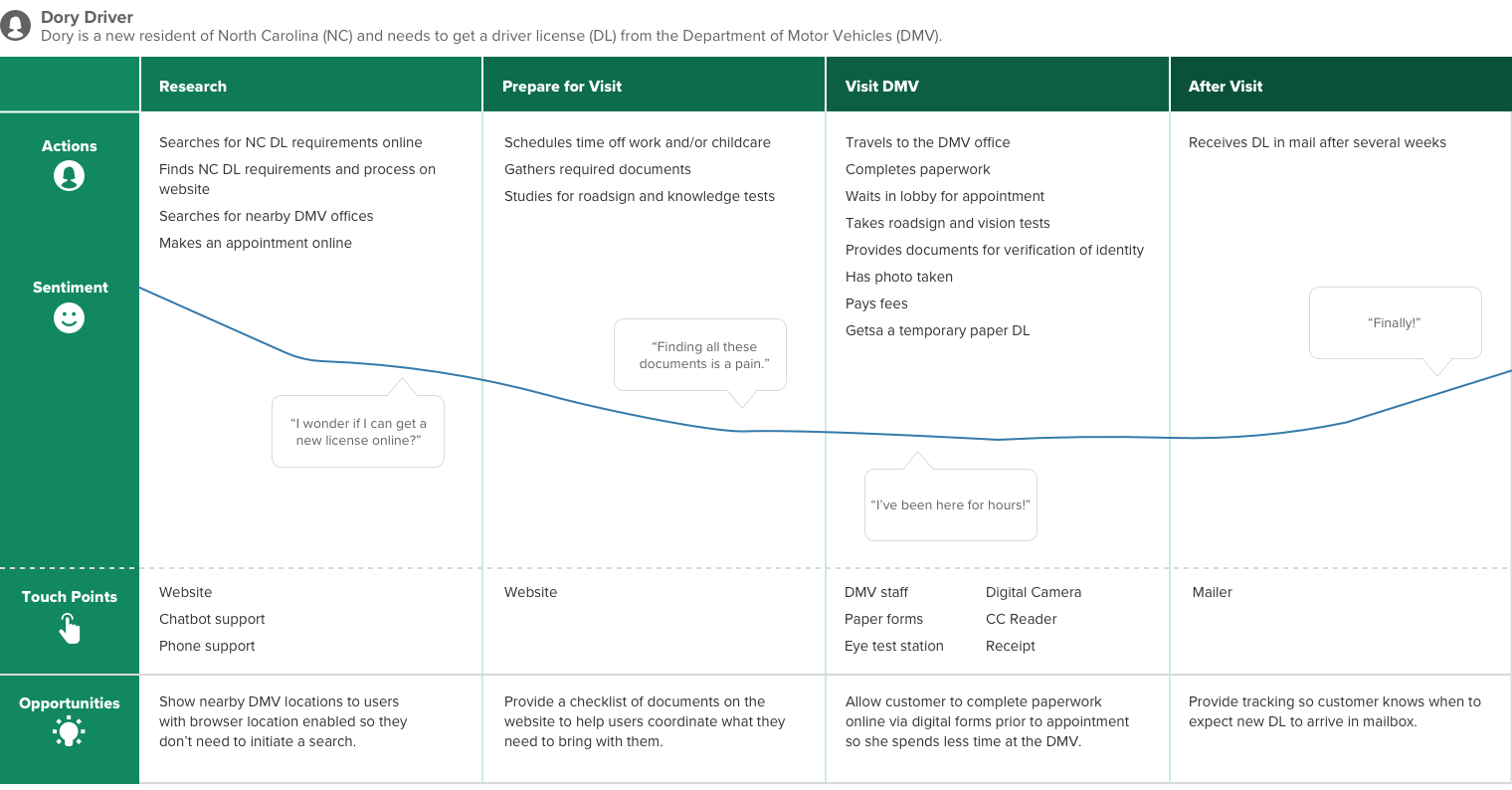

In a journey map, we take what we’ve learned from talking to people about their experiences and use that to list out the full journey a person or group might take to complete a task. We map the touch points, or interactions, they have with the teams delivering that service throughout the process and the sentiment they have about that part of their experience. From there, a team is armed with a visual representation of the journey that they can use to work with teams to help them tackle those opportunities for improvement.

In this example of a driver’s journey to getting a new driver license, we can follow the process from left to right by their actions. The driver begins by searching online for information on how to get a driver license, then searches for a nearby office and schedules her appointment. Next she prepares for her visit, visits the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV), and goes home and waits for her license to be mailed to her. Notice that the driver’s journey includes steps she took to prepare for her visit that have nothing to do with the DMV directly — she takes time off work or arranges for childcare, then searches for her documents. It can be helpful to note these impacts that the service delivery has on real humans who need that service so we can think about ways to reduce that burden.

Next, if you look at the blue line as being on a graph, the y-axis indicates her sentiment — how she’s feeling through the process — while the x-axis represents time throughout the journey. Further down the chart, we’ve listed the touch points, or ways that the driver interacted with the DMV in each stage. Finally, we’ve called out some possible opportunities the agency can take to improve that driver’s experience, such as adding checklists, online registrations, and a progress tracker to alert her when she can expect the card to arrive in the mail.

With this view of the process and the sentiments our users feel when they go through the process, product teams and stakeholders can prioritize their work or further research on the opportunity areas and identify other areas of improvement. Is there a way to make it easier to find and submit the necessary paperwork? How might we reduce the time spent in the DMV office? What would need to change if we wanted to alert people when their card is in the mail? How would someone prefer to be notified? The journey map doesn’t have these answers, but it provides a space to understand the questions we want to ask.

Service blueprinting

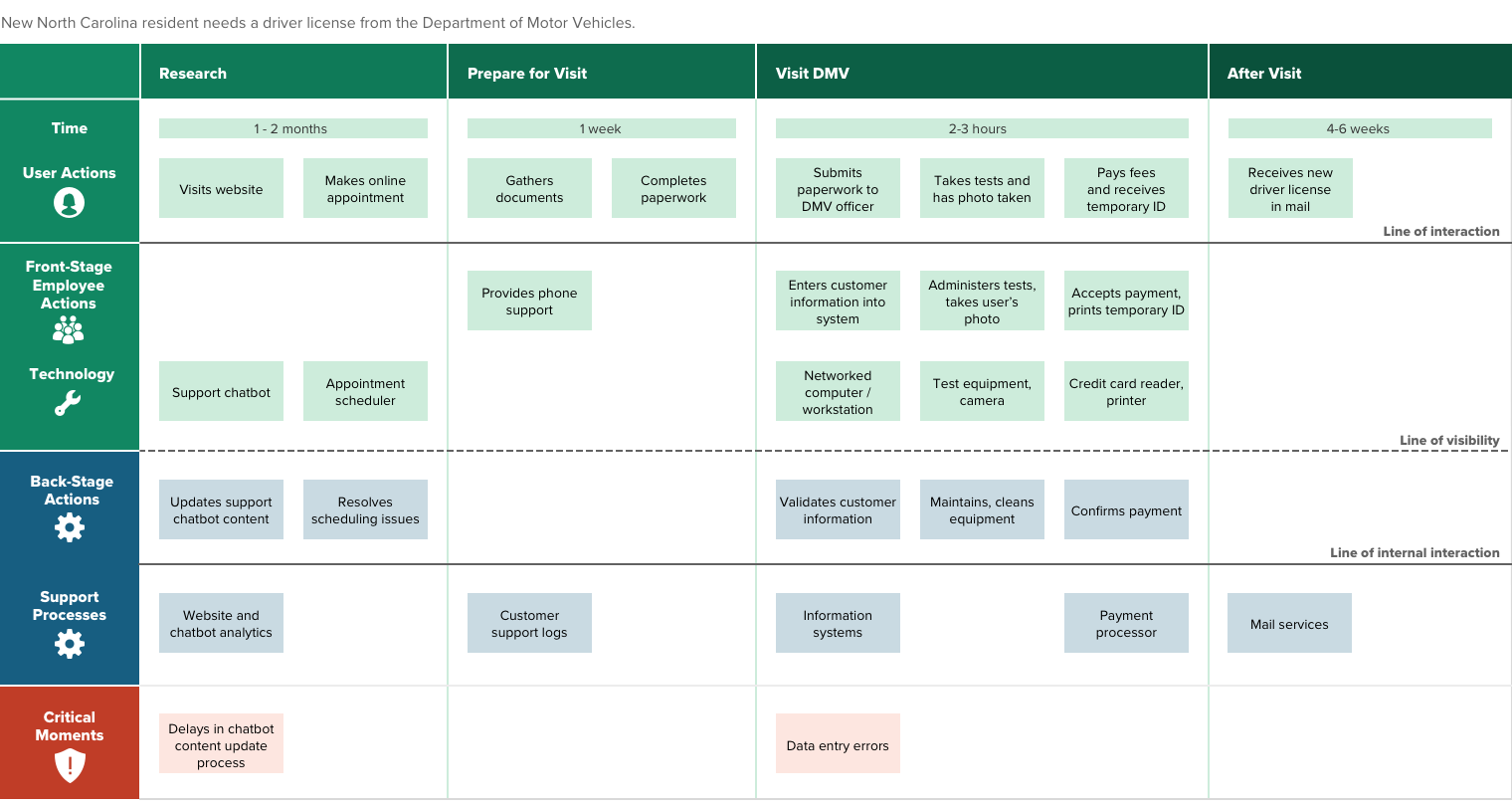

Another valuable service design tool is the service blueprint. A service blueprint goes beyond the user’s journey and experience and maps out all the behind the scenes processes that enable the journey. Just as we only see a small part of an iceberg above the water, a user only experiences a small part of the machinery that goes into delivering a service. The service blueprint maps all of it — both above and below the waterline.

It’s important to note that service design doesn’t just focus on the technical improvements in the journey. Service design is a holistic view and is just as interested in the human and policy aspects of a journey as the technical ones. As such, a service blueprint is a valuable tool to highlight all the processes, policies, teams, and tools that come together to enable the delivery of a service and the areas to improve not just the technology, but also the human and policy processes. Once we understand an existing process and its impacts, we can go a step further and map a recommended future state as a way to visualize a plan and build out a roadmap of improvements.

In our sample service blueprint for a resident getting her driver license, we can again follow our driver’s journey by their actions, and the technology and systems they encounter along the way. This time, however, we go deeper into the other processes and actions that contribute to that journey. Read from left to right, the top rows, marked in green, and above the dotted Line of Visibility, represent the front stage. The front stage actions are those that the driver can see and experience, whether they’re digital services or human interactions with DMV employees.

Below the Line of Visibility, we see the other digital and team actions that happen behind the scenes in the backstage. These are the interactions that are critical to keep the full process moving, but of which the resident has no awareness. Finally, we’ve identified what we called “Critical Moments” in red. Those are the things that need attention to improve a person’s outcome in the journey.

Armed with this level of detailed understanding of the full process of providing a driver licensing service, stakeholders and product teams at the DMV can now zero in on critical moments they can improve, and brainstorm other ways to improve the overall process, or identify which teams provide each part of the service and how they may be able to integrate. What’s causing the need for phone support in the Prepare phase? What do our call logs tell us about the kinds of questions people are asking? Like the user journey map, a blueprint doesn’t provide all the answers, but it does provide the base understanding from which decisions can be made.

For a more detailed primer on service blueprints, you may want to check out this article on Wireframing with Service Blueprints by Ad Hoc UX Designer Laura Theis.

What can teams learn from these techniques?

While a service design diagram on its own won’t untangle the complex policies and processes that we navigate, it’s a valuable tool for illustrating, identifying, and communicating opportunities that teams can leverage to improve services and connect silos.

By zooming out with a journey map or a service blueprint, we can help teams that are responsible for each piece of the journey understand the bigger picture they’re a part of and build empathy for cross-team collaboration. All of these aspects of service design — from understanding the user journey, to sharing insights on areas where a process breaks down or needs improvement, to building empathy across teams — can help teams plan their roadmaps, advocate for a change in policy, or rethink processes.

Ultimately, the goal is to provide a holistic understanding of a process in order to improve the speed, ease of use, and overall experience someone has of a given service. These tools and techniques can help teams reorient service delivery away from the organizational silos they started in and towards processes that make sense for the people who need them.

This is particularly important in government service delivery, where people who are in critical need of government services are often forced to navigate complex, confusing, and disjointed processes in an attempt to meet their needs. It’s in these areas of our social safety net where the most vulnerable are the least equipped to navigate processes that a service design approach can be particularly useful.

At an even broader and more ambitious scale, we can bust out of agency silos and think about designing government experiences that connect different services to each other. That way, we can find opportunities to stack journeys together, such as identifying opportunities to use a family’s tax filing journey to connect them with affordable health insurance. The Federal Customer Service Initiative Team has written in detail about cross-agency journey maps in an effort to show what’s possible and encourage further collaboration across federal agencies.

Up next: Read our second blog post in the service design series that details how we use this same approach with the Veteran Services Platform program to improve our internal systems and processes.

Related posts

- The new Ad Hoc Government Digital Services Playbook

- Four myths about applying human-centered design to government digital services

- Our four day discovery sprint with San Jose

- Ad Hoc and the State of California

- How to use product operations to scale the impact of government digital services

- The building blocks of platforms