Navigating government barriers to human-centered design

For human-centered design folks moving from industry to government work, these constraints can feel like a barrier to designing better services.

Last week, we talked about some examples of how human-centered design techniques can help government teams make decisions and build better services. In this post, I’d like to dig in to the ways government differs from industry when it comes to implementing human-centered design. Understanding the complexity of this work is the best path forward to successfully bringing human-centered design techniques into government.

Serve everyone

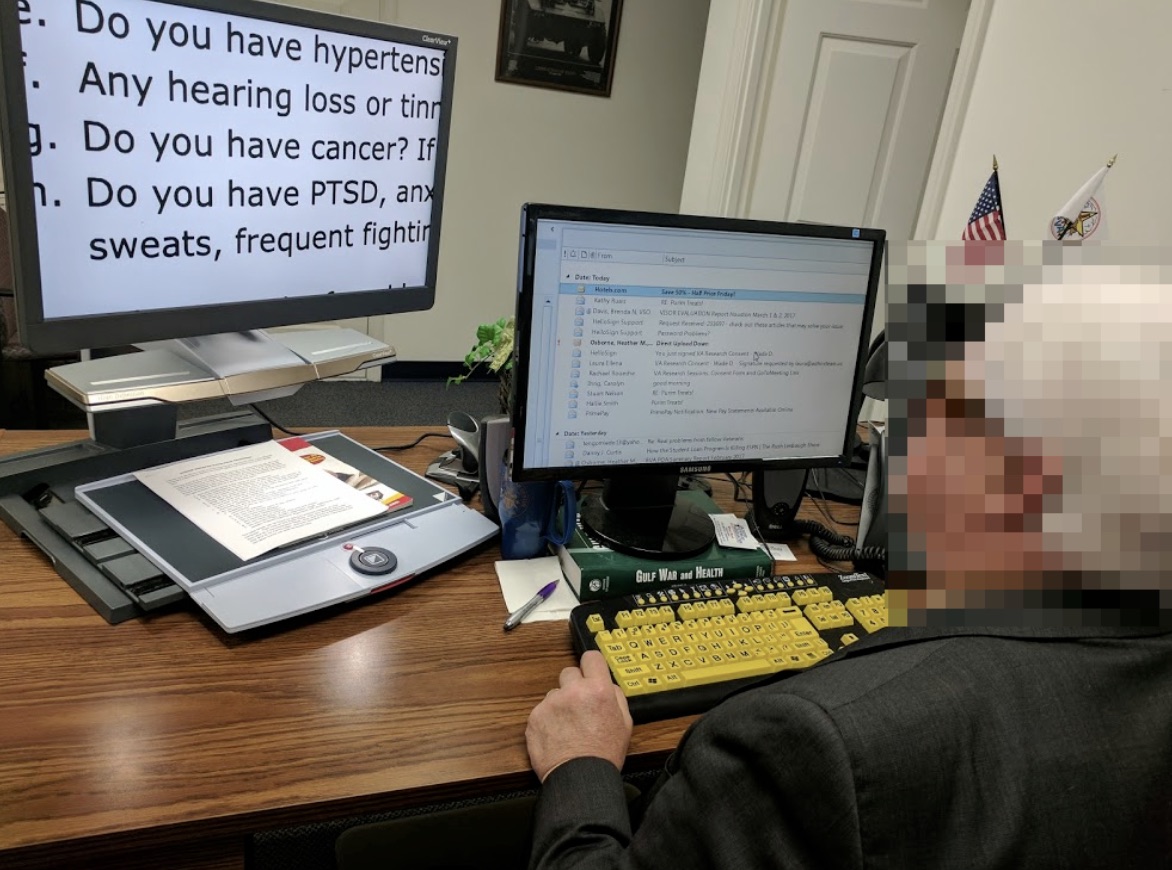

Government has to serve the entire United States. We can’t pick a target audience, or pivot to find a product-market fit. While some agencies have slightly narrower audiences (for example, Veterans and their families or Medicare recipients), they still have a mandate to serve everyone within that audience regardless of cost or digital literacy. For designers, this means widening your definition of users and prioritizing design decisions that work for the largest possible audience.

Accessibility compliance

Government websites are legally required to be accessible to people with disabilities, also known as Section 508 compliance. There can be a big difference between technically compliant and realistically usable, and we believe in building to a higher standard of usability. For example, code that meets the legal requirements for accessibility compliance may not clearly identify the section headers of the page. That makes it difficult for people using a screen reader to find what they’re looking for on a website. Asking someone who uses a screen reader to try your site out can identify small changes that make big improvements in usability.

Accessibility requirements apply to the words we put on websites, too. The Plain Writing Act requires agencies to use clear communication that the public can understand and use. While it’s more work to simplify complex explanations, doing so makes a difference for people trying to get things done on your website.

Paperwork Reduction Act

Work for government is subject to the Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA), which has sometimes incorrectly been interpreted to make user research illegal. For government partners and customers who are new to human-centered design, it’s important to walk through how and when PRA does and doesn’t apply to a project. We recommend pra.digital.gov from the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs as a helpful resource to understand the nuances of the law. Just know that user research is very much allowed — and now the 21st Century IDEA Act even requires that public websites and services are “designed around user needs with data-driven analysis influencing management and development decisions.”

Technology approval

Government teams need internal IT approval to use new technology, so we can’t start using any new tool without making sure it will be approved for them and be accessible within their office firewalls. Approved software varies widely from agency to agency. Some teams communicate on Slack and collaborate through Google Drive while others are working with emailed Word documents and conference calls.

Approvals for new tools can often be slower than is realistic for short- or medium-term projects. This means getting creative with already approved tools and meeting your customers where they are. If you can show the value of human-centered design techniques, government staff can be excellent internal advocates to get better software approved for your next project.

Privacy and data use

There are strict government rules about privacy and data use, especially Personally Identifiable Information (PII) and Protected Health Information (PHI). Part of working on government-scale projects that affect people at critical moments in their life is dealing with sensitive data.

PII and PHI will come up in user research recruiting and testing. Human-centered design teams need to plan how to track data for possible participants and how to edit or redact data before sharing with their teams. Showing you know how to properly handle PII and PHI can go a long way to building trust with government staff new to human-centered design.

Embracing the constraints of government

While these constraints add a lot of things that projects outside of government don’t have to consider, we’ve embraced them as ways we can hold our work to high standards. Accessible websites that are serious about user privacy are more ethical and easier to use. Understanding the nuances of PRA and technology approvals builds trust with government teams and leads to products that work in the real world.

If you’d like to embrace the constraints of human-centered design work in government, check out our open positions.

Related posts

- Human-centered design helps government make better decisions

- What Jurassic Park can tell us about human resilience and human-centered design

- Developers are humans too: Why API documentation needs HCD

- The new Ad Hoc Government Digital Services Playbook

- Four myths about applying human-centered design to government digital services

- UX Offsite 2017 in Portland, Oregon