Faith in the foundations: Lessons from DC history for compassionate design

You can find all kinds of contradictions on 16th Street NW in Washington, DC. Nicknamed “Church Row,” any number of different Christian denominations, as well as Jewish and Buddhist congregations, make their homes along this busy thoroughfare. Population shifts over time have affected the demographics and sects housed on 16th Street but, when one faith community moves out of their building, they frequently pass it on to another faith community.

Photo from Wikimedia Commons by Farragutful. Used under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Photo from Wikimedia Commons by Farragutful. Used under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Take, for instance, the 19th Street Baptist Church, located unapologetically on 16th Street. Formerly the B’nai Israel Synagogue, the Baptist church has the symbolic architecture of two faiths.

Photo from Washington Post by Bill Lebovich.

Photo from Washington Post by Bill Lebovich.

The foyer features a prominent Star of David with Jerusalem at the center. In certain lighting, a robed Jesus casts a stained glass reflection over the star, intermingling symbols of the building’s Jewish past with its Christian present.

In our work designing, building, and maintaining websites, we could take a lesson from the 19th Street Baptist Church, and the many other religious buildings throughout DC that have served as homes for multiple faiths over time. Even as the congregations change, these buildings retain the core of their identities: a spiritual home, a gathering place for a community, a place of respite and sanctuary.

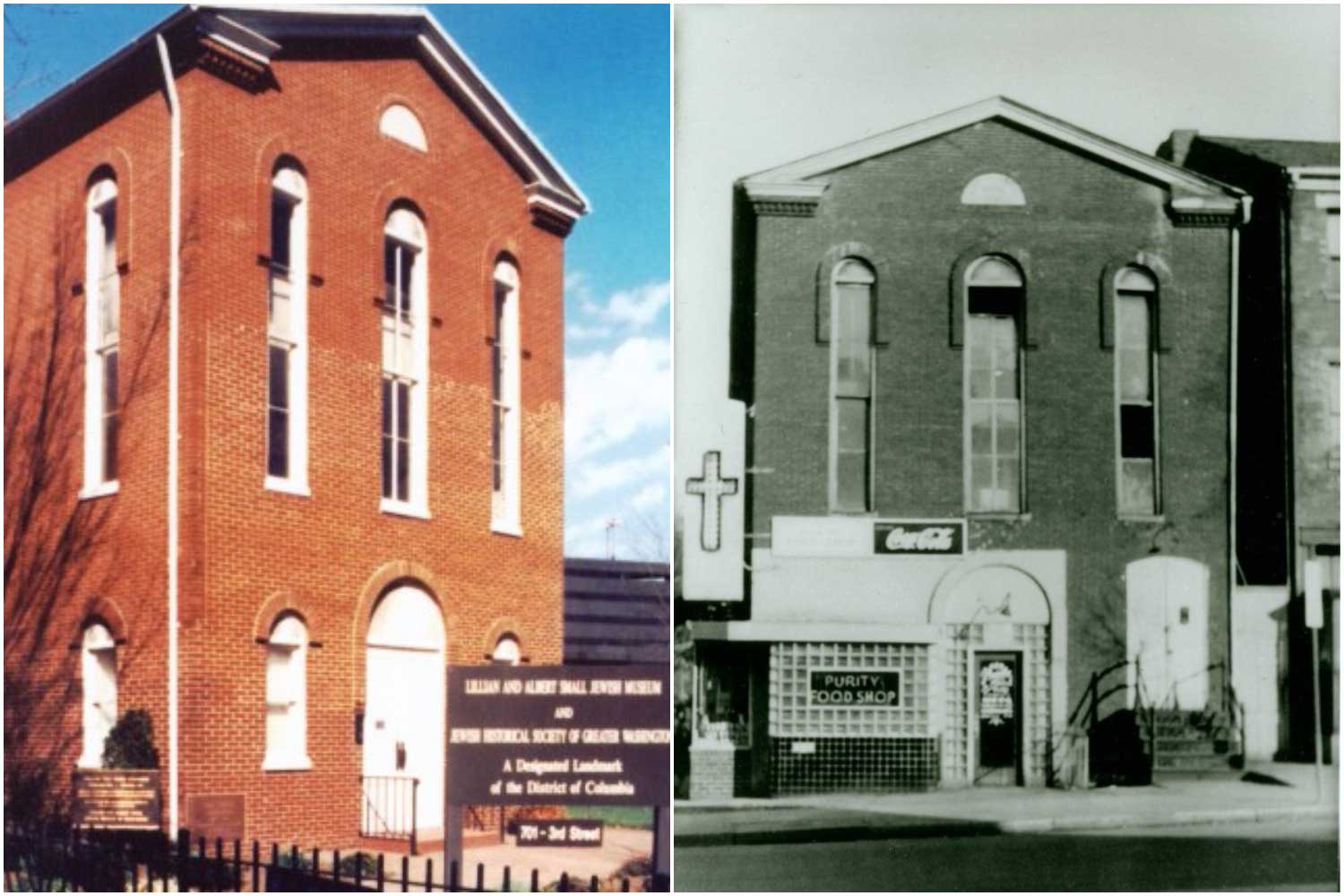

The oldest synagogue in DC, built by Adas Israel in 1876, became a series of churches after Adas Israel moved out in 1908. Photos from the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington photo archives.

The oldest synagogue in DC, built by Adas Israel in 1876, became a series of churches after Adas Israel moved out in 1908. Photos from the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington photo archives.

Just as synagogues transform into Baptist churches, code is written over and repurposed. In either case, the original architects don’t get the last say in what a physical or virtual space can mean for new populations. In our work as government contractors, we must also utilize static, aging or challenging infrastructures to manage the shifting needs of a user community. A common impulse is often to tear the whole thing down. Administrations change, civil servants come into government or retire, priorities shift. The values at the core of our work, and the basic user needs associated with those values, don’t have to.

Rather than tearing websites down to their foundations, we should instead be attentive to core elements that can be repurposed or understood in different ways. Iterative, human-centered design work enables small shifts that not only save the time and expense of starting from scratch, but also ensure we keep the aspects of a site that are already working for users. This also means that repeat users coming back to a website after an overhaul might have to learn a new navigational structure, but not a new way of thinking about the purpose of the site. They will be able to complete the necessary tasks or extract the same value from the site: the trappings change, but the heart, goals, and values should not.

Additionally, another value at the core of our work and that of our government colleagues is trust: any user of a site we built should feel confident that their information is secure and only visible to the people who absolutely need to see it. In moving from early-2000s best practices for website building to those that meet the needs of an audience in 2017, we need to ensure that a visual and information architecture overhaul still provides enough recognizable markers of government for its users to know that the site is legitimate.

Our government colleagues are part of this vital infrastructure. Their depth of knowledge about the subject matter and depth of care for the people they serve are essential to the creation of a web presence with accurate, sufficient information that users want to visit. In many cases, far from allowing government service providers to become entrenched and unchanging, these civil servants have also been working within their spheres of influence to innovate where they can. When we approach a partnership with government with humility, the desire to learn from what already exists, and an openness to hear about our partners’ we can build a stronger home for content and communities.

So, what can web professionals learn from the shared history of synagogues and churches in DC?

Architecture does not define the congregation

Assumptions about “how we’ve always done things” providing the best result for users should be challenged by user experience research. We should dream bigger about the structures that can work well for users and the users themselves. We can look to unrelated fields for best practices that might be effective in our contexts as well.

You don’t have to raze to the foundations to change course

That said, we should value the aspects of existing sites that do work for users. To us, the core of this principle is humility: we may be experts in our practice area, but government partners are experts in their content areas, and users are experts in their lived experiences. We should learn from what already exists, and grow through small, incremental change driven by user research.

There are many right ways to be at home

Before building their own synagogues, Jewish congregations in DC worshipped together wherever they could find space: in homes, in barns, over shops. The container for these rituals changed over time, growing as the congregations grew and moving as the congregation had the money to build or buy space. Along with small, incremental changes to web interfaces, we accept that nothing is permanent, and that our audiences may outgrow later what is best right now. We should seek to learn constantly about our users, and be open to serving them as they are at any given moment.

Related posts

- The new Ad Hoc Government Digital Services Playbook

- How to keep your research practice going in a remote world

- Four myths about applying human-centered design to government digital services

- What Jurassic Park can tell us about human resilience and human-centered design

- Research as Diplomacy: The marriage of research and product

- How to create a welcoming user research environment